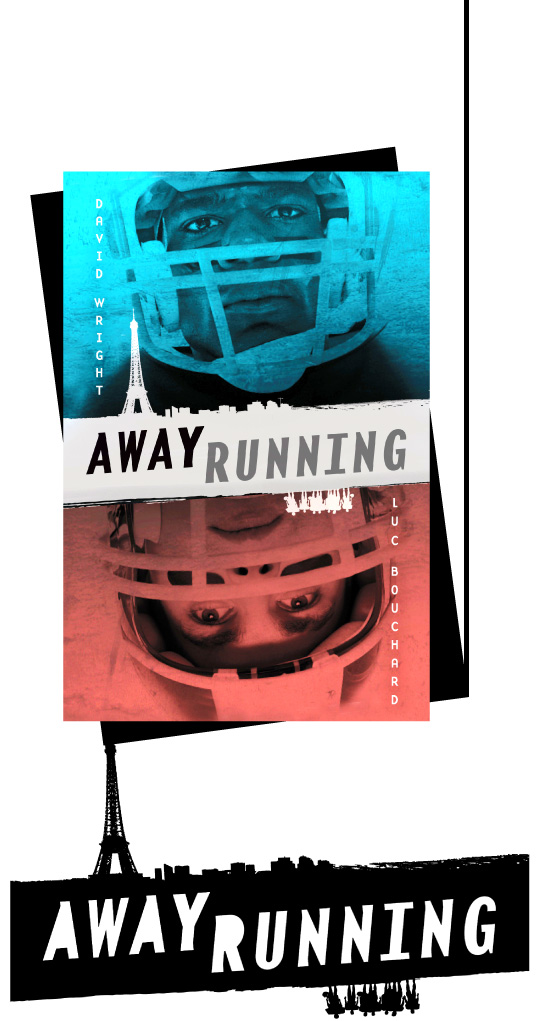

ISBN: 9781459810464 ; Publisher: Orca Book Publishers

Timely, nuanced, and highly respectful of readers’ intelligence.

Kirkus Reviews

Matt and Free discover the dark side of the City of Light.

Matt, a white quarterback from Montreal, Quebec, flies to France (without his parents’ permission) to play football and escape family pressure. Freeman, a black defensive back from San Antonio, Texas, is in Paris on a school trip when he hears about a team playing in a rough, low-income suburb called Villeneuve-La-Grande. Matt and Free join the team, the Diables Rouges, and make friends with the other players, who come from many different ethnic groups. Racial tension erupts into riots in Villeneuve when some of their Muslim teammates get in trouble with the police, and Matt and Free have to decide whether to get involved and face the very real risk of arrest and violence.

Buy the book.

Away, Running

THE BOOK

Canadian Mathieu Dumas and Freeman Behanzin, from Texas, each separately leaves home to go abroad. The two high school players find themselves teammates on the Diables Rouges, an American football club in the fictional suburb Villeneuve-La-Grande. This is one last fling before facing the inevitabilities that await them: college, careers… life.

For the white boy and the black boy, one Canadian and the other American, their friendship blossoms as they explore the cobbled streets and age-old stones of the City of Light. But the relationships that Matt and Free develop in Villeneuve expose them — and our readers — to a side of Paris that’s rarely seen, the Paris of projects and poverty, of class divisions and racial strife. When the police harass and arrest some of their Muslim teammates, the North Americans get swept up in the urban uprising that erupts afterwards.

Before returning to North America to begin careers as writers, the authors of Away, Running, David Wright and Luc Bouchard, played semi-pro American football for the Flash of La Courneuve, outside Paris. When riots broke out in 2005, we both took a plane to witness firsthand the troubles that had ignited in our past home and were spreading across France. The consternation and outrage we encountered and the tales we heard from old teammates told an entirely different story from the one reported in the media.

Away, Running emerged from our experiences. Set against the little-known backdrop of American football in France, the novel uses the riots to dramatize the promise and frustrations of multiculturalism.

With characters we immediately care about, spot on dialogue, and a fast moving plot, Away Running takes readers into the very heart of racial and cultural prejudice.

Elisa Carbone,

award-winning author of Jump

MEDIA / PRESS

Kirkus Reviews

“North American teens join an impoverished Paris suburb’s American football team. After a present-tense opening in which Matt, Free, and their French teammates unintentionally draw aggressive police attention, the prose jumps months backward and into the past tense. Tired of doing what his wealthy mother wants, Montreal quarterback Mathieu—Matt—hops a plane to Paris to play on a French friend’s American football team. The team, made up of marginalized local teens, primarily of North African descent, is allowed two foreign players. The second one recruited is defensive back Free, an African-American exchange student from San Antonio. The lengthy setup delays the football, but once the team’s assembled, Matt and Free work hard alongside team captain Moussa (known as Moose) to turn the scrappy underdogs into winners. But despite growing friendships, they can’t ignore the class and racial discrimination their teammates face, which the North Americans don’t. Subplots—such as Matt’s mild, innocent romance (which contrasts starkly with an early scene of youthful voyeurism)—serve to enhance empathy with characters. Authors Wright and Bouchard, who met playing football in Paris and draw on experience for detailed authenticity, pull no punches in addressing racism and social ills, effectively presenting a complicated situation with no simple solution. Once the story catches up with the present tense, tensions brew into irreversible, violent disaster. Timely, nuanced, and highly respectful of readers’ intelligence.“

Montreal Review of Books

“Away Running follows two very real and likeable seventeen-year-old boys on a trip to Paris. It’s no ordinary backpacking adventure, however.

"Mathieu Dumas from Montreal and Freeman Omonwole Behanzin from San Antonio, Texas, take turns telling the story of their pre-university experience playing football américain in the suburbs of Paris. The team they play for, the Diables Rouges, represents the poor (barely fictional) Parisian suburb of Villeneuve-La- Grande, home to many immigrants from North and sub-Saharan Africa. As the season pushes the team toward the national finals, Matt must confront his privileged background and Freeman, or Free as he’s called, struggles to decide how a recent tragedy will define him. Racial tensions mount in a heartbreaking scene that is all too familiar and very relevant to current affairs. Away Running is highly readable and well written. The two authors, David Wright and Luc Bouchard, met playing football in France and have based the book on similar real-life events from 2005. It’s evident they put a lot of thought and work into telling the story. The two boys and their new friends switch between French and English from France, Quebec, and America. It could have been clunky, but it’s deftly executed without being repetitive and adds another layer to their youthful banter. Each sorrow in the book – a casual racist act, an imperfect reaction to it, the sudden loss of a loved one, deep-rooted injustice – is so well-crafted it will bring a more sensitive reader, ahem, to tears. Yes, it’s also football book. But the fast-paced games are told succinctly and there’s plenty of interpersonal drama to keep things interesting for readers who aren’t sports fans. In the end, football gives the two young men “structure … discipline … and help [to] make better decisions.” They need all this and more when Villeneuve-La-Grande falls apart. “

Booklist

“Paris is the city of light—unless you live in a northern suburb, such as Villeneuve. Matt, an affluent white kid from Montreal, and Freeman, an African American military kid from San Antonio, Texas, learn about the dark side of Paris when they play for the Diables Rouges—an American-style football team. Each 17- year-old is in Paris for a different reason: Matt, to run away from his domineering mother and her plans for his future; Free, to finish a study-abroad program while coping with his dad’s death in Iraq. As the two play with the Diables, they learn about the struggles for North African and Arab immigrant teens and their families. The action-packed book begins just before the championship game; it then rewinds to tell about the boys’ lives, and moves forward through the season. Based on a Parisian tragedy from 2005, the story’s upsetting turn will take many readers by surprise. Introspective yet fast moving, this high/low offering gives teens plenty to ponder.“

The Globe and Mail

“There is a persistent and questionable assumption that books about sports are great for reluctant readers. But that is only true if the reluctant reader happens to like sports. This is a book about football with plenty of appeal for the unreluctant. Seventeen-year-olds, Matt and Freeman are playing American football in a poor Paris suburb where racial tensions are running high between residents and the police. It’s based on the real-life Paris suburb, Clichy-sous-Bois, which Nicolas Sarkozy singled out in 2005 as being full of 'racaille' (scum or riffraff). Co-written by two former football players who played on French teams, it’s a fascinating look at a struggle that many might assume is limited to the southern United States. With short chapters, punchy dialogue and timely subject matter, this is one that even football neophytes will find captivating.“

The Huffington Post

“On occasion I come across a book I want to steal and tell people I wrote it, a book that delivers challenging strings of strong words that deliver dilemmas and consequences, in a style that you hadn’t hoped for, but were glad when it hit you like a bucket of cool water. Away Running, by David Wright and Luc Bouchard, the story of two young football players coming into their own under the backdrop of social turmoil, is one of those books.

"The story opens with Matt, Free and their French teammates confronted with belligerent police officers, only to trip back in time, and space, showing how these young men got to their present situation. Annoyed with a wealthy mother, Montreal quarterback Mathieu (Matt) runs away to Paris and plays for an American football team. The roster is made up of neglected teenagers, primarily of North African descent, and is allowed two foreign players via the rules of their club. The second foreign player is defensive back Free, an African-American exchange student from Texas. Matt and Free work with team captain Moussa (a truly fun character known as Moose) to turn this squad of underdogs into a force to be reckoned with. As friendships and relations flourish, the characters become inundated with the heart of the conflicts of Paris and their own lives. Classism and racism come to light as subplots of romance flesh out this character driven story and supply the reader with something tangible to hold on to.

"Authors Wright and Bouchard, who met playing football in Paris and draw on personal experience to add detail and realism to this fictional story, address complicated social realities with grace, while leaving the reader room to explore these ideas and come to their own conclusions, and once the story slides back to the present violence boils over in an all too real picture. The reader sees this coming, hopes it doesn’t happen, but knows it will. It had to. That is the kind of storytelling one finds in Away Running.

"This book has fire behind the words that sneak up and burn you down when you least expect it. Away Running is complicated and thought provoking, a book of physical untamed words. It also has poetry, and asks questions that should be discussed openly, and never swept under the rug of readers. Orca publishing has a winner on its hands, it should be celebrated and talked of in a way that makes a reader want to steal the story and call it their own. I did, and so will you.“

School Library Connection

The two main protagonists of this book, Matt and Free, are Canadian and American expatriates living in Paris. Taking time off to play American style football for a team in an impoverished suburb of Paris, they learn more about life and themselves than football as a series of events leads up to the 2005 Paris riots. This book does a very realistic job of portraying the two youths, in alternating points of view, who become involved in the events leading to the flashpoint of the riots. Racism and prejudice against religions, ethnic persuasions, and classes are portrayed in a believable manner that highlight how often our attitudes toward groups influence our behaviors and words without us even being aware of it. The book contains some profanity and references towards sexual feelings and situations, but it is not excessive. Every group is represented with complexity and has both redeeming and negative qualities, except maybe the drug dealer. The French is interpreted so language isn't a problem.

"Highly Recommended"

Quill and Quire

“The new novel by Luc Bouchard and David Wright tackles the subject of racism and adversity faced by American football players in the early 2000s in Villeneuve, a poverty-stricken neighbourhood of Paris. Away Running also explores the rising tensions between the marginalized Parisian poor – primarily Muslims and immigrants of North African descent – and the police. The story is told through the eyes of Matt and Free, American teens who become the first two foreign players on the Diables Rouges, Villeneuve’s American football team.

"As the book opens, the police catch Matt, Free, and some of their French teammates trespassing. The situation escalates toward disaster, and the scene ends with a cliffhanger. The story then backtracks three months, as Bouchard and Wright fill in the events that have brought the characters to this point, narrated from the alternating perspectives of Matt and Free. Moussa (or “Moose”), the team’s captain, some of their teammates, friends, and family are also ably brought to life. Honest, amusing banter dances around the tensions between classes, religions, and races in a rich blend of slang and colloquialisms that render the teammates sympathetic and realistic.

"The infusion of football throughout gives the novel a framework and lexis, however the sport itself isn’t played very often. Inconsistencies with pacing and tense are also distracting. Nevertheless, the authors, who draw on true events and their own experiences playing football overseas, address complex situations and social tensions in a manner that is true-to-life and potent.

Resource Links

“Away Running begins and ends with running away. The opening scene presents Matt (Mathieu Dumas from Montreal) and Free (Freeman Omonwole Behanzin from San Antonio, Texas) and some of their teammates on the American football team, the Diables Rouges, in Villeneuve, France. Villeneuve is a suburb of Paris noted for its mainly poor, immigrant population, and a concomitantly high level of racial tension. Taking a short-cut through a construction zone, the boys are stopped - unfairly accosted - by the police. Immediately, readers are im- mersed in the fear these teens face: they have done nothing wrong, but they know that doesn’t matter. They will be arrested. Their parents will be called. They will not be able to play in the under-20s championship final in four days. They run.

"Matt, too, is running. His mother is an editor for a Canadian women’s magazine; his brother and sister have both been successful in busi- ness; Matt is similarly slated to attend Orford College - an excellent business school with no sports: no football. Stealing from his college funds, Matt runs to his football friend in Paris.

"Free is in Paris on a summer-school study- abroad trip, on scholarship and feeling ostracized from his white classmates. When he meets Matt, and is given the opportunity to stay and play for the Diables Rouges, he jumps at the chance. But Free, too, is running from the reality of his life in the United States.

"Much of the novel is taken up with the relationships among Matt and Free; Moussa (Moose), their closest team-mate; the volatile Sidi and his sister Aïda; and the other teammates, who both respect the ’Ricains for their playing abilities and resent them for their privilege. Away Running demands not only that readers consider issues of privilege and race, but also that they understand how deeply embedded our cultural ethos lies, and how complicated intercultural and interracial interactions really are. The prejudice the Diables Rouges players and their community experience is not ultimately about race, pure and simple, as Matt learns. Despite being African-American, Free is not persecuted with Moose and Sidi and the other non-White players. Being foreign, regardless of colour, sets him out- side of the cultural dynamics at play in the lower-income Paris suburbs at the same time as his race - as well as being from a similarly low-income, oppressed 'hood 's San Antonio - allows him to understand those dynamics more than Matt can.

"Issues of race, of cultural understanding, of teens’ social relations are set against the American football season in Paris. The Diables Rouges are a middle-of-the-pack team, and much of the boys’ growth in under- standing results from their involvement in the team as they develop to meet their potential. What makes this more than a 'there is no I in team' story is the true human messages that the authors impart through the carefully and very successfully developed characters. We really get to know not only Matt and Free, but Moose and Aïda, and the full cast of narrative support. We become fully invested in their lives long before the final scenes are played, before Away Running stops being about football at all, and becomes entirely about race, culture, politics, and police brutality. It was not surprising to learn from the Authors’ Notes at the back of the book that the final scenes are based on a real incident in France in 2005. It is to the authors’ great credit that the violence of the final scenes, the gross unfair- ness of the situation, flows seamlessly out of the entirely fictional characters and storyline they have created.

"Away Running is a book about football, best suited for teenaged boys who will engage with the mentality and language of these fictional teenaged boys from the disadvantaged spaces of their cities. But it is far more than that: at its heart, it is a book about what it means to be human, regardless of class, race, or ethnicity. A football book that moved me to tears; I never thought I’d see that."

Other Reviews

This is an important book. With characters we immediately care about, spot on dialogue, and a fast moving plot, Away Running takes readers into the very heart of racial and cultural prejudice.

Elisa Carbone, award-winning author of Jump.

Bouchard and Wright have delivered a fascinating insider look at a slice of Parisian life that you never read about. They take you inside the neighborhoods, cliques, conflicts and team huddles as you follow these young men finding their place in the world. Away Running will excite young and old alike — as electrifying and satisfying as a last second winning touchdown!

Billy Hicks, former NFL Europe executive and general manager of the London Monarchs.

Away Running is a richly complex mix of personal growth against a backdrop of social upheaval. Read it. Remember it. Recommend it.

Raymond Obstfeld, co-author with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar of the Street Ball Crew middle-grade book series.

Away Running is an impactful story about courage and the importance of learning to take a stand and doing what is right. Turning the pages, I asked myself again and again what would I do if it was me in Matt and Free’s shoes.

Mark Weigthman President & CEO of the Montreal Alouettes (CFL)

Bouchard and Wright have delivered a fascinating insider look at a slice of Parisian life that you never read about...

Away Running will excite young and old alike.

Billy Hicks, former NFL Europe executive and general manager of the London Monarchs

Honest, amusing banter dances around the tensions between classes, religions, and races in a rich blend of slang and colloquialisms that render the teammates sympathetic and realistic.

Quill and Quire

CONTACT

READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

TEACHER'S GUIDE

PARIS RIOTS 2005

On October 27, 2005, in the Parisian suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois, three boys were electrocuted after climbing into an Éléctricité de France substation, running away from the police. They had been guilty of nothing more than growing up in a poor, racially mixed and crime-ridden neighborhood, one feared and marginalized by the rest of French society.

Just minutes before, the boys had been playing a pick-up game of soccer on a pitch near their high-rise projects. It was the end of Ramadan—the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, a time of daytime fasting—and with the sunset, the group of boys, many of whom were Muslim, were walking home for supper. After passing a padlocked construction site, the boys found themselves suddenly surrounded by police cars. A neighbor had called in to report (mistakenly, it turns out) that the boys were vandalizing the property. The police, armed with Flash-Balls—guns that fire rubber bullets—rushed up on them, ordering them to stop and produce their ID documents.

Tensions had been running high in Paris’s poor suburbs like Clichy-sous-Bois. Populated largely by immigrants, many from France’s former colonies in North and sub-Saharan Africa, the townships had become a toxic combination of all the country’s social ills: a decaying urban landscape, pockmarked with overpopulated and poorly maintained high-rise projects; widespread under- and unemployment; inferior education; juvenile delinquency; and crime. In a speech the week before, Nicolas Sarkozy, France’s interior minister (who would be elected president a few years later), had made sweeping and disparaging statements about the projects, describing its hip-hop-identified young residents as “racaille.” Commonly translated as “scum,” the word can also mean “vermin.” Sarkozy vowed to “nettoyer les cités aux Karsher”—to clean out the high- rise projects with a power hose, the language evoking the work done by an exterminator.

Relations between neighborhood residents and the police quickly deteriorated. Sarkozy assigned the CRS—the riot squads, which have a reputation for viciousness—to police these neighborhoods. Frequent and repeated checks of identity documents became commonplace. Residents perceived the CRS presence as being intended to intimidate, not to protect.

When the police cars sped up on the group of boys in Clichy-sous-Bois, three of them— Muhittin Altun, seventeen, Zyed Benna, seventeen, and Bouna Traoré, fifteen—panicked. Fearing the overly aggressive police as much as the eventual wrath of their parents for getting arrested, they ran. Muhittin, Zyed and Bouna sprinted past the graffiti-covered wall of a cemetery, the police chasing after them. What ensued sparked riots throughout France that lasted nearly a month.

An impactful story about courage and the importance of learning to take a stand and doing what is right.

Mark Weigthman President & CEO of the Montreal Alouettes (CFL)

Publication manager : Luc Bouchard

Email : lucbouchard@videotron.ca

Phone : 1.514.969-3229

Hosted by :

OVH

S.A.S. au capital de 10 000 000 €

Siège social : 2 rue Kellermann - 59100 Roubaix - France.

Tél. : + 33 (0)9 72 10 11 12

Created by:

Atelier Bleu Banquise

58, rue Sadi Carnot – 17500 Jonzac – FRANCE

Tél. +33 (0) 5 46 49 28 96

e-mail : production@bleubanquise.com